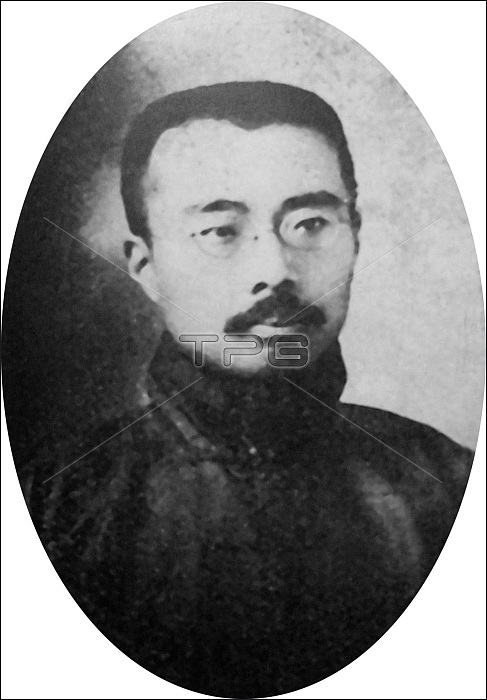

Writing essays in vernacular Chinese for the influential magazine La Jeunesse, Zhou was a key figure in the May Fourth Movement. He was an advocate of literary reform, and called for literary reform. In a 1918 article, he called for a 'humanist literature' in which 'any custom or rule that goes against human instincts and nature should be rejected or rectified'. As examples, he cited children sacrificing themselves for their parents and wives being buried alive to accompany their dead husbands. Zhou's ideal literature was both democratic and individualistic. On the other hand, Zhou made a distinction between 'democratic' and 'popular' literature. Common people may understand the latter, but not the former. This implies a difference between common people and the elite. His short essays, with their refreshing style, have won him many readers since then up to the present day. An avid reader, he called his studies 'miscellanies', and penned an essay title 'My Miscellaneous Studies'. He was particularly interested in folklore, anthropology and natural history. He was also a prolific translator, producing translations of classical Greek and classical Japanese literature. Most of his translations are pioneering, which include a collection of Greek mimes, Sappho's lyrics, Euripides' tragedies, Kojiki, Shikitei Sanba's Ukiyoburo, Sei Sh?nagon's Makura no S?shi and a collection of Kyogen. He considered his translation of Lucian's Dialogues, which he finished late in his life, as his greatest literary achievement. He was also the first one to translate (from English) the story Ali Baba into Chinese (known as Xian? Nu). He became chancellor of Beijing University in 1939.

| px | px | dpi | = | cm | x | cm | = | MB |

Details

Creative#:

TOP27039130

Source:

達志影像

Authorization Type:

RM

Release Information:

須由TPG 完整授權

Model Release:

No

Property Release:

No

Right to Privacy:

No

Same folder images:

Loading

Loading